The Untold Stories of Venezuelan Military Prisoners: Torture Beyond the Four Prison Walls

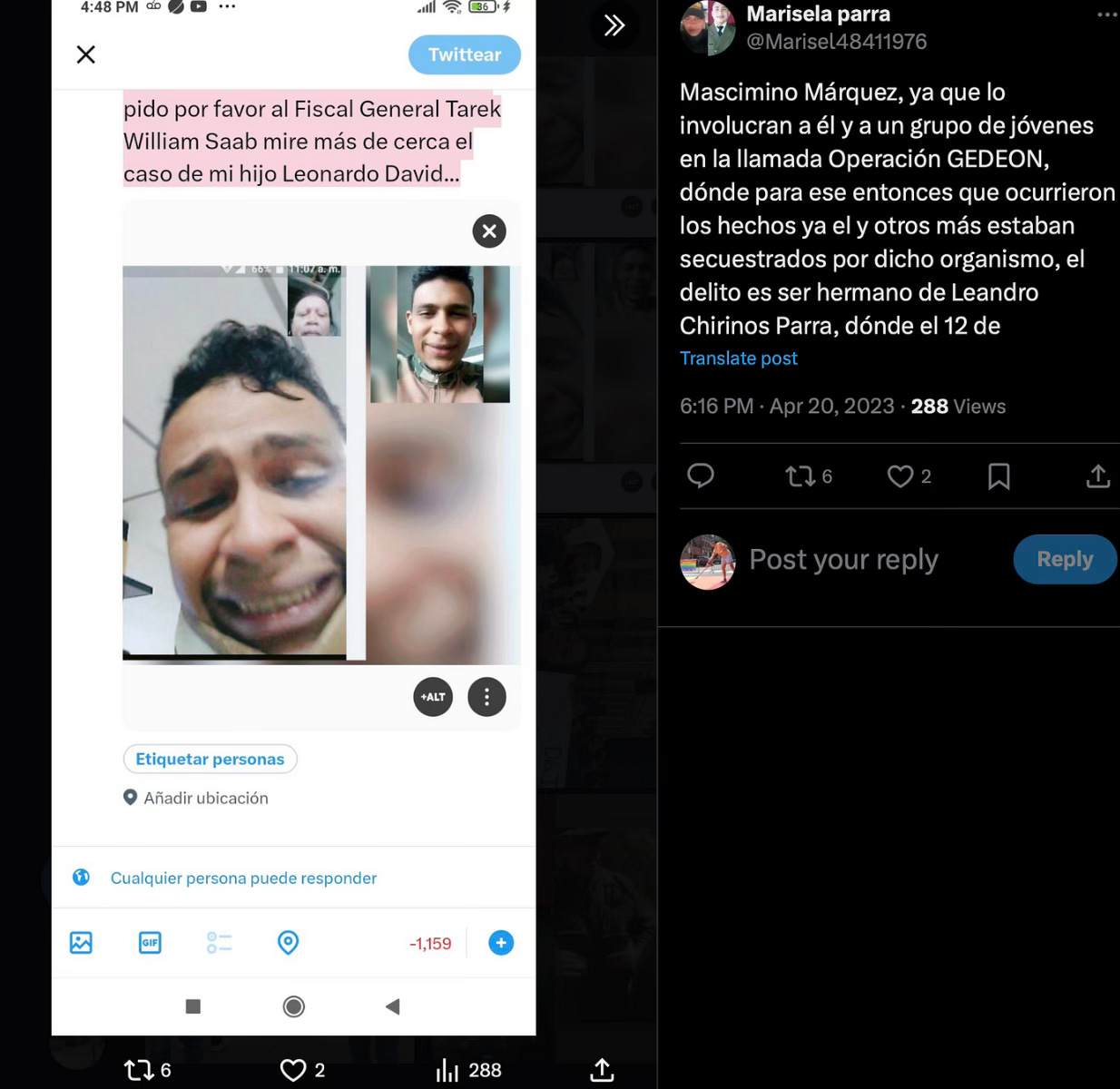

“If I did not give them what they were asking for, they were going to kill my son,” said Parra, who recounted hearing the screams of her son pleading for help.

For nine days Marisela Parra had no clue where her son’s whereabouts were in Venezuela. It was only after receiving a video call from an unknown number showing her son physically beaten by military guards that confirmed her fears–he was now in the hands of the Maduro regime.

Leonardo Chirinos, who served as a military officer in the Venezuelan General Directorate of Military Counterintelligence (DGCIM), was detained by members of the DGCIM under the allegations of conspiring with his brother in the assassination plot against President Nicolás Maduro, known as Operation Gideon.

“If I did not give them what they were asking for, they were going to kill my son,” said Parra, who recounted hearing the screams of her son pleading for help. “They were looking for his brother, they wanted me to turn him over!”

The operation back in 2020 centered on a ploy of military scale, led by two U.S. Green Beret veterans and nearly 60 Venezuelans who planned to launch both air and ground assaults on Maduro’s mansion, as previously reported by the Associated Press. They attempted to siege the northern tip of Venezuela in the city of Maracaibo, with two fishing boats–the plan failed.

The outcome of the operation led to the killing of eight Venezuelan members off the coastal town of Macuto, along with the arrest of 13 members, including the two American veterans involved in the coup attempt.

DGCIM officers were looking for Leonardo’s younger brother Leandro Chirinos, who at the time, was the sergeant of the Bolivarian National Guard–a military branch that reports to the Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Interior, Justice, and Peace. He was forcibly taken by the DGCIM agents.

Both brothers are faced with separate charges related to treason to the homeland, mutiny, incitement to military rebellion, and against military decorum, according to court documents obtained by Foro Penal, a watchdog organization in Venezuela.

In a moment of desperation and fear for her eldest son’s life, she decided to take screenshots of the encounter over the video call, as she witnessed her son with a piece of cardboard strapped around his neck, asking for her brother’s phone number.

She described her next steps, only driven by her faith in God and her love for her two children. “I had to speak up, these are my sons, and if I didn’t do it, who else would have?” Parra posted the image of her son pleading for his life online, asking the nation’s prosecutor Tarek William Saab to drop the charges.

Instead, after nearly four years, she has still not seen her two sons and has fled the country under clandestine conditions. “At one point I was being followed...I had to be careful with my next steps.”

Both brothers, like many political prisoners, have been separated from their families along with 17 other prisoners, who were recently transported to El Rodeo III, a detention center located in Zamora, North East of Venezuela’s capital Caracas.

Through 11 months of independent investigative reporting, the whereabouts of the prisoners, along with the testimony and provisions of government and domestic documentation have been acquired.

This took place five days after the nation’s presidential elections took place on July 28 of this year — he was previously being held in a detention center known as Hombre Nuevo.

Leandro was arrested on May 11, 2020, and is currently being held at El Helicoide, according to documents provided by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, an organization centered on international and local affairs.

The facility, which was intended to be a shopping mall in the 1950s, has instead been filled with political prisoners who have dissented against the dictatorship and in some cases are still awaiting public trial under the legal jurisdiction of Venezuela’s penal code, with its own track record of human rights violations within the confines of the prison cells.

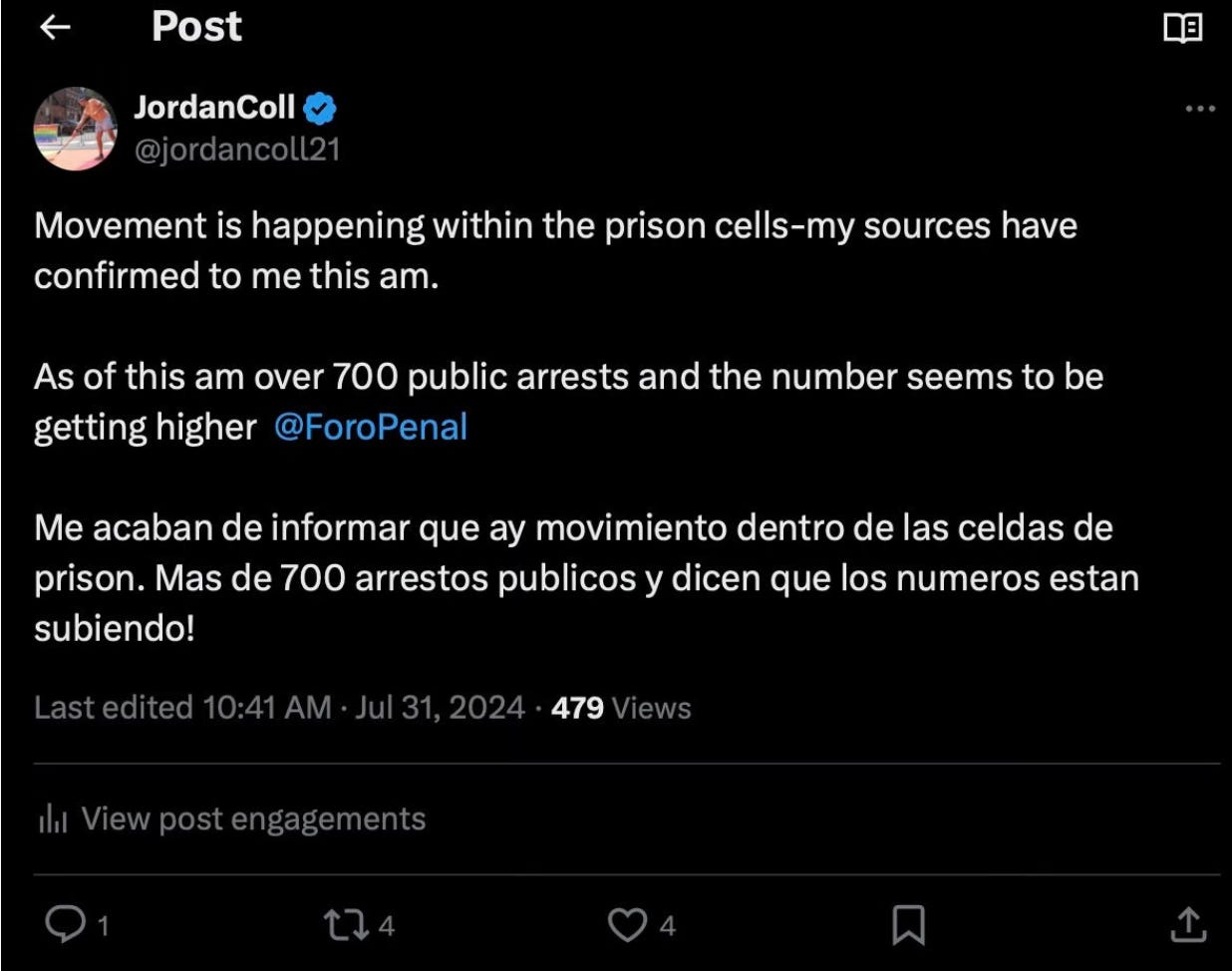

Venezuela’s recent presidential elections, over two weeks ago, showed the regime’s expected cry for victory in favor of extending the regime’s corruptive mantel within the bounds of their own government.

But the outcry for democracy superseded the will of the regime, which was evidently shown when former lawmaker and opposition leader Maria Corina Machado, who was barred by the Maduro-led Supreme Tribunal of Justice from running in the presidential elections for the next 15 years, showed the world the voter receipts.

The National Electoral Council is one of the five branches of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, which claimed Maduro had received 6.4 million votes against Gonzalez with 5.3 million votes on his side.

An independent analysis conducted by the Associated Press, determined opposition leader Edmundo Gonzalez “received 6.89 million votes, nearly half a million more than the government says Maduro won with. The tabulations also show Maduro received 3.13 million votes from the tally sheets released.”

After Maduro took power in 2013, he would eventually cause a ripple in the political landscape of Venezuela, leading to the arbitrary arrests of over 15,000 individuals between 2014 and 2023, according to data by Amnesty International, a human rights organization.

But the question remains whether the political prisoners, subjected to various forms of torture and human rights violations throughout the years of the regime, will be set free and if a reversal of the regime’s authoritarian practices can happen in a nation where the regime has taken over the will of the people for over a decade.

As of August, a group of around 125 political-military prisoners who served in military ranks for the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, have been arrested, according to one report provided by the nonprofit organization Families of Political Prisoners in Venezuela (FPPM), a list of military political prisoners are faced with sentences ranging from six to 30 years, under the jurisdictional framework of the Venezuelan Penal Code.

“It would take the restructuring of our entire judicial system to hand back democracy to our nation,” said Yakeline Herrera, an attorney at Foro Penal, who is taking on the case of Leonardo Chirinos (whose birthday is on Aug.22), charged with conspiracy to overthrow the government and association to commit a crime, a sentencing of 21 years in prison.

“All of the cases have been stopped,” said Herrera, in an exclusive interview, who explained that the regime had paused all jurisdictional proceedings, in the wake of the protestors taking to the streets during the elections.

In the case of Leandro Chirinos who was seen on a video posted on X, formerly known as Twitter, with a military guard, asking him several questions related to Operation Gideon, calling him a “stateless person” and shouting at him “this is now your patriarch!

An abuse of human rights, both physical and psychological, lends itself beyond the four prison walls, as expressed by many of the family members of political prisoners interviewed for this story. Many of the members of those still imprisoned fled Venezuela due to fears of retaliatory efforts under the instruction of the regime.

“We, the relatives of those deprived of liberty and members of various organizations, are writing to you with the purpose of exposing a set of demands regarding what we consider to be illegitimate deprivations of liberty and inadequate conditions of confinement for the so-called prisoners, politicians, prisoners of conscience and victims of human rights violations,” read a recent letter drafted by family members of political prisoners to the nation’s prosecutor Tarek William Saab.

The Venezuelan prosecutor in a recent press conference, days before the presidential election of the nation stated, “that only one electoral power exists, just like any other nation.”

Cases like these in Venezuela are not estranged from the practice of systematic torture of political prisoners ushered in by members of the DGCIM, to both civilians and military personnel alike. In one instance, a woman by the name of Yusimar Elisneth Montilla Ortega, served as the Army Second Sergeant of the Bolivarian National Guard, according to prison and medical records obtained.

She was arrested on June 15, 2019, by DGCIM agents, for being involved in an alleged plan against the governor of the state of Monagas in Venezuela, known as Operation Caso Gobernadora de Monagas.

Two days later, she was brought before the Tribunal Courts in Venezuela in charge of overseeing military cases under the charges of alleged crimes of treason to the country and instigation of rebellion, according to a September report released by Foro Penal.

The charges carried a sentence of 7 years and nine months at the Eastern Penitentiary Center of Venezuela, known as La Pica, located in the northeastern state of Monagas–five other military members were also given the same sentencing.

That same year, in August, the 24-year-old, who was 7 months pregnant at the time, according to medical records, was forced to perform a cesarean medical procedure at the hospital Maturín Central. She gave birth to a girl, but in less than 24 hours, DGCIM agents stepped in to separate the child from her mother and returned her to the prison cell.

The relative of Antonio José Sequea Torres who served under the National Bolivarian Army had a black veil placed over her head by prison guards, before walking in to see Torres–similar to claims made by other relatives of political prisoners visiting their loved ones.

When the veil was removed, he was right in front, found in a bright orange prison suit was there in front of her, said his sister Fatima Sequea in an exclusive interview. “They torture our loved ones, to torture us,” she said.

An investigative report, released by the Venezuelan Observatory of Prisons (Observatorio Venezolano de Prisiones-OVP), looked into the conditions of 31 of Venezuelan’s 52 prison systems, in their findings, they concluded that eight of those detention centers were controlled by prison bosses, referred to as “pranes.”

In Maduro’s efforts to appease the nation of its current conditions, he is seen eating soup on live national television, stating that Venezuelans are in a better place, but the reality– is far from this truth.

“I don’t even have money to buy myself a bar of soap in here,” one prisoner said within the prison walls–the identity has not been disclosed due to fear of retaliation efforts from the regime. “I’m starving in here, and each day is harder than the next,” a prisoner who participated in the assassination drone attempt on Maduro back in 2018.

Another prisoner, who wished not to be identified said that their requests for medical attention for a general gynecology checkup have been actively denied, “I have received no medical consultation, with countless requests denied,” a year ago through a blood test the individual was diagnosed with Hepatitis. “I have tried to find outside help, it’s not enough!”

The prisoners are a couple who had been separated and arrested due to public demonstrations at their universities against the regime. Within the scope of those arrests, an estimated 9,000 individuals have been deemed by the Maduro regime as political prisoners, deprived of their humanitarian rights in reports released by a watchdog group, Foro Penal.

As in the case, of many Latin American countries, the prison system in Venezuela has faced overcrowding, a shortage of staff members, and a regression of human rights.

For nearly a decade, reports on the Maduro regime have caught the eye of the international community as a result of the “killings consistent with previously documented patterns of extrajudicial executions and other violations in the context of security operations,” according to a recent human rights report laid out by the U.S. Department of State.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) launched an investigation in 2018 at the request of six nations; Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Peru, Paraguay, and Canada. The inquiry was centered on the rising allegations related to practices dealing with crimes against humanity in the region of Venezuela–which asked to look into potential allegations of systematic tortuous practices.

“These disappearances are not the most classical or traditional, in which people have gone missing for years, at times decades,” said a senior human rights officer at the United Nations, stating that oftentimes, the individuals are often found deceased under the instruction of the regime.

The Venezuelan constitution has been altered 27 times throughout the nation’s 200-year history. “Constitutional reform became a means of legitimizing an illegal and often violent change in the government rather than representing a true constitutional shift,” wrote Luis Sales, a professor from Florida International University, who has researched Venezuela’s judicial and governmental systems.

“Everything started on May 18, 2018,” said Luis De La Sotta, a former navy captain, who was detained by DGCIM officers, for nearly “five years, 4 months, and 11 days,” as the captain who survived, recounts being pointed at gunpoint by military officers he had trained with him, asking him to hand over his carry-on firearm, and that the DGCIM would interview him back at their headquarters in Caracas. “The interview never happened,” said the captain, instead they “tortured me for names.

Prior to his arrest, he received a text message 24 hours before they detained him, informing him that DGCIM agents were on their way to arrest him–he decided to stay. “I did nothing wrong, all I did was go against the bloodshed and massacre this man [Maduro] has left on our people.”

Kept in the dark chambers of the DGCIM headquarters, where he was placed in a two-by-two wooden chamber spending hours there without food or any sunlight for seven days straight, and then eventually a month, he held onto the vivid memories he had with his family, who had no idea where their father or husband was.

After the fourth day in that facility, he was presented in front of the Tribunal Court handling military cases, one beaten and bleeding captain with no right to a private attorney was brought in front of the judge–his crime, “defying atrocities brought by the regime.”

He pleaded not guilty and denounced the nature of the regime–which he said was ravaged by crimes against humanity and acts of torture to Venezuelans. The law requires under the penal code of Venezuela to have a first hearing within 48 hours, according to the captain, he was presented on the fourth day–a violation of the Venezuelan Penal Code. He was found guilty and sent back, where he said the physical and psychological tortures persisted within the four prison walls.

“They would hand out books on Fidel Castro, at one point the bible,” recalled Sotta, who said, at one point DGCIM agents threatened his family by claiming they would rape his wife and imprison his 17-year-old son at the time of his capture. “I just remembered the happiest moments with my family, in a place filled with so much misery and hate...I was thrown to the floor and left there to die like an animal.”

After spending two years at the Boleita, the torture detention site at the DGCIM headquarters, he would be transferred over to Fort Tiuna or Fuerte Tiuna, until he was liberated on September 2023.

He commends the efforts of his sister for her perseverance in bringing the case to the public and said that he was unsure where he would be if it weren’t for her outcry to the press, and anyone who would listen.

“Having my brother back was the most liberating gift a sister could ask for, to hold him once more in my arms, was worth all the outcry and fight we put up together,” said Molly De La Sotta, who is the current president and founder of nonprofit organization Families of Political Prisoners in Venezuela (FPPM).

“The republic of Venezuela that once existed no longer is there,” she said in a press conference addressing members of the InterAmerican Institute for Democracy.

In the streets of Times Square last year, Leyla Ave Blanca, a native of Venezuela, was among several protestors denouncing the war crimes and humanitarian rights violations committed by the administration of Nicolás Maduro — who has served as the president since 2013.

“These are like my children,” said Blanca, who pointed at images of members who were beaten and tortured by supporters of Maduro’s military as they opposed the practices brought by the dictator. “This government has destroyed our way of life in Venezuela, he [Maduro’s regime] has left our people in ruins, and we are here against his power.

“There is nothing worse for a political prisoner than to be forgotten,” said Francisco Marquez, former political prisoner and the senior advisor for Voices of Memory- a Venezuelan organization created by journalist and former politician Victor Navarro. “I don’t think people really understand that Maduro serves as a figure of Saddam Hussein when it comes to torture.”

Important story. Thanks for the hard work!